Cancer Types Explained!

- Mr_Solid.Liquid.Gas

- Jun 24, 2025

- 14 min read

Updated: Jul 22, 2025

A Guide to Understanding Cancer

This guide is here to help you learn — not diagnose! 💬 If you’re feeling unwell or have concerns, please talk to your doctor or medical practitioner. This article is for education only and is not a replacement for medical advice. 🩺

To help you get the most out of this guide, we’ve included:

🧠 Keyword Highlights at the beginning of each chapter

📘 A Glossary of Terms at the end

If a term is bolded or listed as a keyword, you'll likely find it defined in the glossary. We recommend you gloss-over these keywords and check the glossary prior to reading a chapter!

Ready to explore? 🚀🔬🧪🥼⚛

By Phystro.com — Making Science Understandable and Human

Chapter 1: What Are Cancerous Cells?

Keywords: *Cancer, cell growth, cell division, cell cycle, mutation, oncogene, tumour suppressor gene, TP53, apoptosis, benign tumour, malignant tumour, metastasis, lymphatic system, bloodstream, DNA damage, hallmarks of cancer, proliferative signalling, invasion, angiogenesis, molecular biology, tumour.*

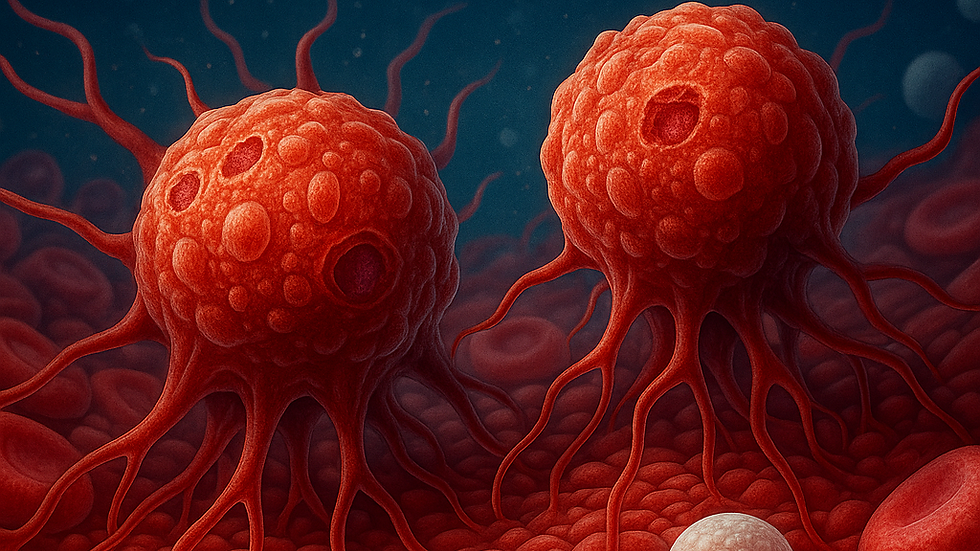

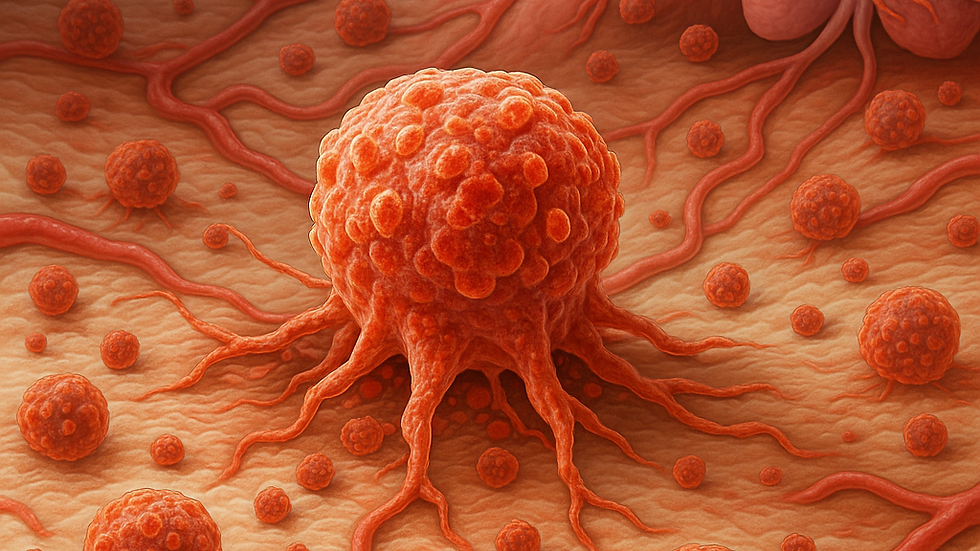

Cancer is not a single disease. It is a group of disorders characterised by abnormal and uncontrolled cell growth. Typically, human cells divide in an orderly manner. This orderly division supports growth, replaces old or damaged cells, and maintains tissue integrity. This regulation relies on a system of genes and proteins that guide the cell cycle. They also initiate repair mechanisms and induce cell death when necessary.

Cancer arises when this balance breaks down. A cell becomes cancerous after acquiring mutations that allow it to bypass normal growth controls. These changes enable it to evade programmed cell death (apoptosis) and proliferate indefinitely. These mutations often affect key genes—oncogenes and tumour suppressor genes. Oncogenes promote growth when mutated or overexpressed. Tumour suppressor genes normally hinder uncontrolled division. A notable example is the TP53 gene, known as the “guardian of the genome.” This gene plays a critical role in detecting DNA damage. When mutated, cells may continue dividing with accumulated errors and form a tumour.

Tumour Types: Benign vs Malignant

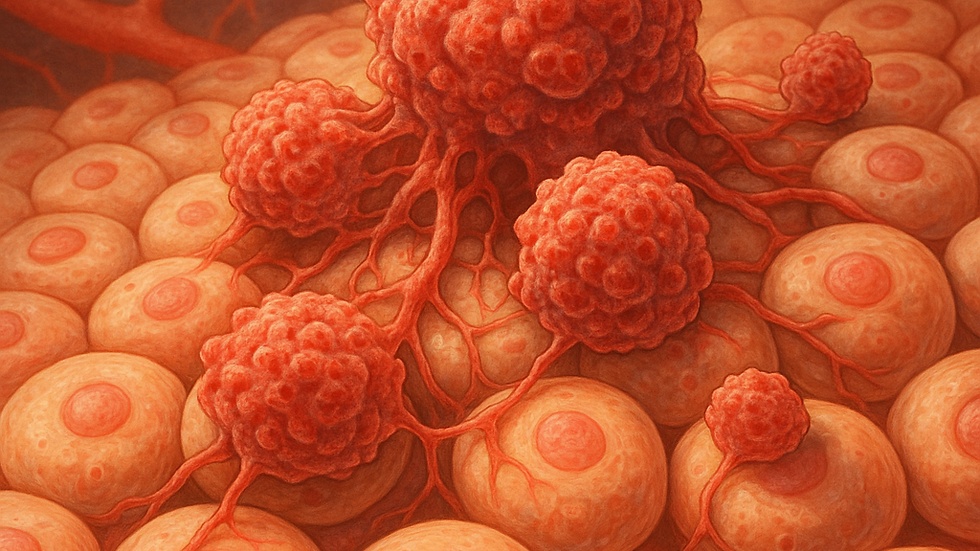

Not all tumours are cancerous. A benign tumour may grow, but it lacks the ability to invade surrounding tissues or spread throughout the body. In contrast, malignant tumours invade nearby structures. They can enter the bloodstream or lymphatic system, seeding secondary tumours in distant organs. This process, known as metastasis, makes cancer especially dangerous and challenging to treat.

On a molecular level, cancer cells exhibit distinct behaviors—known as the hallmarks of cancer. These include resistance to cell death, sustained proliferative signalling, and the ability to invade and metastasise. Additionally, cancer cells recruit blood vessels to supply growing tumours (angiogenesis). These traits make cancer a complex, adaptive disease, forming the foundation for many modern treatments targeting specific pathways involved in tumour growth.

Chapter 2: When Does It Become Cancer?

Keywords: Hyperplasia, dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, invasive cancer, basement membrane, lymphatic system, vascular channels, biopsy, pathologist, CT scan, MRI, PET scan, tumour markers, TNM system, tumour staging, lymph nodes, metastasis, early-stage cancer, advanced cancer, prognosis, systemic therapy, radiation.

The transition from a normal cell to a cancerous one is typically gradual. This transformation follows a stepwise progression in which a cell accumulates genetic and epigenetic changes over time. In early stages, abnormal growth is referred to as hyperplasia. This condition involves increased cell proliferation without structural changes. As more mutations accumulate, the growth can progress to dysplasia. In dysplasia, cells begin to appear irregular and lose their normal arrangement.

If left unchecked, this abnormal tissue may progress to carcinoma in situ. This condition refers to a localised mass of cancerous cells that has not yet invaded the basement membrane separating it from surrounding tissues. Once the tumour breaches this barrier, it is termed invasive cancer. This stage indicates the potential to spread through lymphatic or vascular channels.

Diagnosing Cancer

Diagnosing cancer involves a combination of clinical, imaging, and molecular techniques. A biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosis, where tissue samples are examined under a microscope by a pathologist. Imaging technologies such as CT scans, MRI, and PET scans help determine tumour size and location. Blood tests may reveal tumour markers—molecules produced by cancer cells or in response to their presence.

Staging cancer is crucial for determining treatment options and prognosis. The TNM system is widely used and assesses:

T (Tumour): Size and extent of the primary tumour

N (Nodes): Whether lymph nodes are involved

M (Metastasis): Whether the cancer has spread to distant sites

Early-stage cancers (Stages I or II) are often localised and may be curable with surgery or radiation. Advanced cancers (Stages III or IV) usually require systemic therapies and have a higher risk of recurrence.

Chapter 3: Different Types of Cancer

Keywords:* Breast cancer, hormone receptors, estrogen, progesterone, HER2, targeted treatments, lung cancer, non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), small-cell lung cancer (SCLC), EGFR, ALK, colorectal cancer, polyps, invasive tumour, brain tumour, glioma, glioblastoma multiforme, primary tumour, secondary tumour, leukaemia, bone marrow, white blood cells, acute leukaemia, chronic leukaemia, prostate cancer, PSA test, melanoma, melanocytes, pancreatic cancer, prognosis.*

Cancers are classified based on the tissue or cell type from which they originate. Each type exhibits its progression, molecular characteristics, and treatment strategies. Below are common types of cancer:

Breast Cancer

This form typically begins in the ducts or lobules of the breast. It may be classified based on the presence of hormone receptors (estrogen and progesterone) or the HER2 protein. These classifications influence the cancer's behavior and response to targeted treatments. Symptoms include a lump in the breast, nipple inversion, or changes in breast shape or texture.

Lung Cancer

Lung cancer is divided into two major categories: non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small-cell lung cancer (SCLC). NSCLC is more common and may present mutations in genes like EGFR or ALK. Symptoms often include persistent coughing, chest pain, shortness of breath, or coughing up blood.

Colorectal Cancer

This cancer arises from the inner lining of the colon or rectum. It commonly progresses from benign polyps to invasive tumours through a series of identifiable genetic mutations. Signs include changes in bowel habits, blood in the stool, or unexplained weight loss.

Brain Tumours

Brain tumours can be primary (originating in the brain) or secondary (metastatic). Gliomas, such as glioblastoma multiforme, are especially aggressive. Symptoms may include seizures, personality changes, or neurological deficits, depending on the tumour's location.

Leukaemia

Leukaemia is a cancer of the blood-forming tissues, primarily the bone marrow. It leads to the overproduction of abnormal white blood cells, and it can be either acute (rapid onset) or chronic (slow-growing). Common symptoms include fatigue, frequent infections, and easy bruising.

Other prevalent cancers include prostate cancer (detected via PSA blood tests), melanoma (a dangerous skin cancer from melanocytes), and pancreatic cancer, often diagnosed at a late stage with a poor prognosis.

Chapter 4: Treatment Options – How We Fight Cancer

Keywords: Cancer therapy, tumour type, tumour stage, genetic profile, surgical treatment, solid tumours, open surgery, laparoscopic surgery, robotic surgery, da Vinci robot, chemotherapy, cytotoxic drugs, bone marrow, hair follicles, immunosuppression, cisplatin, doxorubicin, paclitaxel, intravenous delivery, oral delivery, intrathecal delivery, radiotherapy, external beam radiation therapy (EBRT), linear accelerator, proton therapy, brachytherapy, targeted therapy, imatinib, BCR-ABL, trastuzumab, HER2 receptor, immunotherapy, checkpoint inhibitors, pembrolizumab, PD-1, CAR T-cell therapy, hormone therapy, tamoxifen, androgen-deprivation therapy, testosterone, complementary treatment, nutritional support, pain management, psychological care.

Modern cancer treatment is highly individualized, depending on the tumour's type, stage, and genetic characteristics. Typically, treatment involves a combination of approaches aimed at eliminating cancer cells while preserving healthy tissue.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical intervention is most effective for localised solid tumours. Surgeons aim to remove the tumour along with a margin of healthy tissue to ensure complete excision. Techniques vary from traditional open surgery to minimally invasive laparoscopic procedures. In some cases, robotic systems like the da Vinci robot enhance precision.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy involves using cytotoxic drugs that target rapidly dividing cells. While effective against cancer, these drugs also damage healthy tissues, including hair follicles and bone marrow. This can lead to side effects like nausea, hair loss, and immunosuppression. Agents such as cisplatin, doxorubicin, and paclitaxel are commonly used and can be delivered intravenously, orally, or intrathecally.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy uses high-energy radiation to destroy cancer cells by damaging their DNA. External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) is the most common method, utilizing linear accelerators. More precise methods, like proton therapy, minimize damage to nearby healthy tissues. Brachytherapy involves placing radioactive sources close to or within the tumour for optimal effect.

Targeted Therapies

Targeted therapies are designed to disrupt specific molecules involved in tumour growth and survival. For instance, imatinib targets the BCR-ABL fusion protein in chronic myeloid leukaemia, while trastuzumab blocks the HER2 receptor in certain breast cancers. These treatments typically have fewer side effects compared to chemotherapy as they selectively attack cancer cells.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy represents a significant advancement in cancer treatment by activating the immune system against cancer cells. Checkpoint inhibitors, such as pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1), enable immune cells to recognize and attack cancer. Another approach, CAR T-cell therapy, modifies a patient's T-cells to better target cancer. Although promising, these treatments can lead to severe immune-related side effects and require careful management.

Hormone Therapy

Hormone therapy is used in cancers that depend on hormones for growth, like breast or prostate cancer. Drugs such as tamoxifen block estrogen receptors, while androgen-deprivation therapy reduces testosterone in prostate cancer. These therapies can slow cancer progression and may be used alongside surgery or radiation.

Complementary treatments, such as nutritional support and psychological care, play a vital role in enhancing quality of life during and after treatment.

Chapter 5: How AI Could Help Us Detect Cancer Earlier

Keywords: Artificial Intelligence (AI), machine learning, medical imaging, mammograms, CT scans, MRIs, LYNA, metastatic breast cancer, lymph nodes, liquid biopsy, circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA), biomarkers, early detection, screening programs, asymptomatic cancer, risk prediction models, genetic profile, lifestyle factors, family history, personalised screening, preventive strategies, treatment planning, therapy selection, data analysis, patient outcomes.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is transforming cancer detection, analysis, and monitoring. In medical imaging, machine learning algorithms interpret mammograms, CT scans, and MRIs with remarkable accuracy. They often identify patterns unnoticed by human radiologists. Google's LYNA, for example, has demonstrated over 99% accuracy in detecting metastatic breast cancer in lymph nodes.

Early Detection Through AI

AI enhances early detection using liquid biopsies—blood tests identifying circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) or other biomarkers before tumours become visible on scans. These tests, combined with AI-based data analysis, could revolutionise screening programs by catching cancers in asymptomatic stages.

Moreover, AI is utilized for developing risk prediction models considering a patient’s genetics, lifestyle, and family history. These models guide clinicians in personalising screening schedules and preventive strategies.

In treatment planning, AI can aid in selecting therapies based on a tumour’s genetic profile. It may also predict which patients are likely to respond positively to specific drugs. Although still developing, AI's integration into cancer care holds promise for improving patient outcomes.

Chapter 6: Supporting Someone With Cancer

Keywords: Cancer diagnosis, emotional support, presence, listening, grief, fear, anger, practical help, hospital appointments, meal preparation, prescription management, psychological support, mental health, communication, patient autonomy, treatment decisions, lifestyle choices, diagnosis disclosure, support network, emotional well-being.

Being diagnosed with cancer can be an emotionally overwhelming experience.

Support from loved ones is crucial. The most effective way to support someone with cancer is often by simply being present. Listen without jumping to offer quick solutions, allowing them the space to express their fears, anger, or grief.

Practical help, such as transportation to hospital appointments, meal preparation, or prescription management, can relieve daily stress.

Importance of Psychological Support

Psychological support is equally important. Encourage open dialogue about feelings, but avoid pushing them to remain positive at all times. Each person’s cancer journey is unique, and ups and downs are natural.

Respecting their autonomy is vital. Patients should lead decisions regarding treatment, lifestyle, and disclosure of their diagnosis. Your role is to provide support—not to dictate their choices.

Chapter 7: Supporting Yourself When a Loved One Has Cancer

Keywords: Caregiver support, emotional toll, anxiety, depression, burnout, care responsibilities, emotional well-being, support network, caregiver groups, self-care, routines, exercise, sleep, journaling, isolation, healthy boundaries, mental health, emotional resilience.

Supporting someone with cancer can take a significant emotional toll on caregivers. They often experience anxiety, depression, or burnout while balancing care responsibilities with their own lives.

Acknowledging Your Feelings

The first step in self-support is acknowledging your feelings as valid. It’s normal to feel overwhelmed, uncertain, or guilty about prioritising your own needs. Building a support network—through friends, family, or caregiver groups—can help mitigate feelings of isolation.

Prioritising Self-Care

Self-care is crucial. Maintain routines that bring you comfort, whether through exercise, sleep, journaling, or time alone. Setting healthy boundaries is essential for sustaining support over the long term without emotional or physical exhaustion.

Chapter 8: Cancer in the Future – Precision and Prevention

Keywords: Precision medicine, prevention, genomic sequencing, genetic profile, personalised treatment, side effects, treatment efficacy, cancer vaccines, HPV, cervical cancer, throat cancer, hepatitis B, liver cancer, immune system, tumour targeting, robotic surgery, AI diagnostics, treatment optimisation, early detection, cure rates, access disparities, cancer research, survival rates, quality of life.

The future of cancer care is rooted in precision medicine and prevention. Advances in genomic sequencing allow for tailored treatments based on a patient’s unique genetic profile. This shift from one-size-fits-all protocols to personalised medicine aims to minimise side effects while maximising efficacy.

Preventive Strategies

Preventive strategies are improving continuously. Vaccines against cancer-causing viruses—like HPV for cervical and throat cancer and hepatitis B for liver cancer—demonstrate significant public health value. Researchers are exploring vaccines that may train the immune system to specifically target cancer cells.

On the surgical front, robotic systems are enhancing tumour removal accuracy. AI continues to assist in diagnostics and treatment optimisation. One of the most exciting advancements includes refining early detection techniques to catch cancer before it spreads—at the stage where cure rates are highest.

While challenges, such as treatment side effects and access disparities, remain, the trajectory of cancer research is optimistic. Survival rates are improving significantly. Quality of life for many patients has also increased dramatically. Through the collaborative efforts of science, technology, and compassion, we move toward a world where cancer is not only treatable, but preventable.

It is with great thanks and reverence to the incredible research teams, support networks, and charities that help individuals and their loved ones through their cancer journeys.

If you can spare the time, please check the various donation and action pages for the UK-based charity Cancer Research UK.

Other notable causes, like Macmillan Cancer Support, provide essential tailored support.

📘 Glossary of Terms

Below is an alphabetically ordered glossary of all key terms mentioned throughout the article:

AI diagnostics – Use of artificial intelligence to assist in identifying diseases from imaging, pathology, or genomic data.

ALK – A gene that can mutate and drive cancer growth, especially in lung cancer.

BCR-ABL – A fusion gene found in chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) leading to uncontrolled cell growth.

CAR T-cell therapy – A treatment where a patient’s T cells are modified to better recognise and attack cancer cells.

CT scan – Computed tomography scan, a medical imaging technique for detailed internal views.

DNA damage – Injury to the cell's genetic material, potentially leading to mutations and cancer.

EBRT – External Beam Radiation Therapy, using focused beams of radiation for cancer treatment.

EGFR – A gene that can mutate and contribute to cancer, often targeted in lung cancer treatment.

HER2 – A protein that, when overexpressed, can lead to aggressive breast cancer.

HPV – Human papillomavirus, a virus linked to several cancers including cervical and throat cancer.

IV delivery – Intravenous delivery, administering medication into a vein.

MRI – Magnetic Resonance Imaging, a technique for detailed images of internal body structures.

PD-1 – A protein that, when blocked by drugs, enhances immune response against cancer.

PET scan – Imaging technology that observes metabolic processes in the body.

PSA test – A blood test used to screen for prostate cancer.

TP53 – A gene that regulates the cell cycle and prevents tumour formation, often mutated in cancer.

acute leukaemia – A rapidly progressing blood cancer producing immature white blood cells.

advanced cancer – Cancer that has spread from the original site to other body parts.

androgen-deprivation therapy – Treatment reducing male hormones (androgens) to slow prostate cancer growth.

angiogenesis – The formation of new blood vessels; in cancer, this process supplies tumours.

apoptosis – Programmed cell death that removes damaged or unnecessary cells.

asymptomatic cancer – Cancer that does not cause noticeable symptoms in its early stages.

basement membrane – A thin structure separating epithelial tissue from underlying tissue.

benign tumour – A non-cancerous growth that does not spread.

biopsy – The removal of tissue for microscopic examination to diagnose disease.

bone marrow – Tissue inside bones that produces blood cells.

brachytherapy – A type of radiotherapy placing a radioactive source near or inside the tumour.

care responsibilities – Tasks involved in providing care for someone with a serious illness.

checkpoint inhibitors – Drugs that enable immune cells to attack cancer.

chronic leukaemia – A slow-growing leukaemia form that may take years to progress.

cisplatin – A chemotherapy drug preventing cancer cell replication by crosslinking DNA.

colorectal cancer – Cancer originating in the colon or rectum.

complementary treatment – Supportive therapies improving quality of life alongside conventional treatments.

cytotoxic drugs – Medications that kill or damage cells, used in chemotherapy.

da Vinci robot – A robotic system for performing minimally invasive surgeries.

data analysis – Interpreting medical or genetic data to guide decisions or discoveries.

depression – A mood disorder causing persistent sadness and loss of interest.

doxorubicin – A chemotherapy drug inhibiting DNA replication.

dysplasia – Abnormal cell growth, often associated with precancer.

early detection – Identifying cancer at an early, treatable stage.

emotional support – Help addressing the psychological impact of illness.

epigenetic changes – DNA modifications affecting gene expression without altering the sequence.

exercise – Physical activity supporting mental and physical health.

external beam radiation therapy – Directing radiation at the tumour from outside the body.

family history – Genetic predisposition to diseases based on relatives’ conditions.

fatigue – Extreme tiredness, common among cancer patients.

genetic profile – Set of genetic characteristics unique to an individual or tumour.

genomic sequencing – Analyzing DNA to identify mutations and tailor treatment.

glioblastoma multiforme – An aggressive brain tumour with a poor prognosis.

grief – Emotional response to loss, common among patients and families.

hair follicles – Skin parts that grow hair, often affected during chemotherapy.

hallmarks of cancer – Traits defining cancer cells, such as uncontrolled growth.

hormone receptors – Proteins on cancer cells binding to hormones influencing cell behavior.

hormone therapy – Treatment blocking or removing hormones to slow cancer growth.

imaging – Techniques providing pictures of the inside of the body.

imatinib – A targeted drug used to treat chronic myeloid leukaemia.

immune system – Body’s defense system enhanced by immunotherapy to fight cancer.

immunosuppression – Reduced immune activity due to some cancer treatments.

immunotherapy – Treatment stimulating the immune system to combat cancer.

invasive cancer – Cancer spreading beyond its original tissue.

journaling – Writing for self-reflection and emotional processing.

laparoscopic surgery – Minimally invasive surgery using small incisions.

leukaemia – Cancer of blood-forming tissues, including bone marrow.

lifestyle choices – Habits influencing cancer risk or recovery.

lifestyle factors – Personal lifestyle aspects affecting cancer risk.

linear accelerator – A machine delivering high-energy radiation for treatment.

liquid biopsy – Blood tests detecting cancer biomarkers like ctDNA.

listening – Actively paying attention to someone’s words and emotions.

liver cancer – Cancer beginning in liver cells.

lymph nodes – Structures filtering lymph and trapping cancer cells.

malignant tumour – A cancerous growth that invades and spreads to other tissues.

mammograms – X-ray images used to diagnose breast cancer.

melanocytes – Pigment-producing cells in skin; origin of melanoma.

melanoma – Serious skin cancer developing from melanocytes.

mental health – Emotional and psychological well-being.

metastasis – The spread of cancer from primary sites to distant organs.

minimally invasive surgery – Procedures using small incisions for reduced recovery time.

molecular biology – Study of biological activity at the molecular level.

mutation – A change in DNA that can lead to cancer.

nausea – Common chemotherapy and radiotherapy side effect.

oncogene – A mutated gene that promotes uncontrolled cell growth.

oral delivery – Taking medication by mouth.

paclitaxel – A chemotherapy drug stabilising microtubules and inhibiting cell division.

pain management – Controlling pain using therapies or medications.

pathologist – A doctor diagnosing diseases through tissue examination.

patient autonomy – Patient's right to make informed decisions about care.

personalised screening – Tailored screening plans for individuals.

personalised treatment – Therapies designed based on genetics or tumour biology.

practical help – Assistance with daily tasks for someone undergoing treatment.

precision medicine – Treatment approach based on genetic and lifestyle factors.

preventive strategies – Actions taken to reduce cancer risk.

primary tumour – Original site where cancer begins.

progesterone – A hormone influencing breast cancer development and treatment.

prognosis – Likely course and outcome of a disease.

prostate cancer – Cancer in the prostate gland of men.

psychological care – Support focusing on mental and emotional health.

radiotherapy – Treatment using high-energy radiation to kill tumours.

risk prediction models – Models estimating an individual’s cancer risk.

robotic surgery – Using robotic systems for surgery.

screening programs – Organised efforts to detect cancer in populations.

secondary tumour – A tumour forming from cancer spreading.

self-care – Activities promoting health and wellness.

sleep – Essential for recovery mental and physical health.

solid tumours – Abnormal tissue masses without liquid areas.

support network – People providing practical and emotional help.

supportive therapies – Non-curative treatments easing symptoms.

surgical treatment – Removing cancerous tissue through operation.

systemic therapy – Treatment reaching cancer cells throughout the body.

tamoxifen – A drug treating breast cancer by blocking estrogen receptors.

targeted therapy – Drugs targeting specific cancer cell genes or proteins.

testosterone – Hormone involved in prostate cancer development.

therapeutic planning – Designing optimal strategies for treating conditions.

throat cancer – Cancer developing in the throat, including the pharynx or larynx.

treatment efficacy – How well a treatment achieves its intended result.

tumour – Abnormal tissue growth, benign or malignant.

tumour markers – Substances indicating potential cancer presence in blood or tissue.

tumour staging – Assessing cancer size and spread to determine severity.

tumour suppressor gene – A gene protecting against cancer development.

vascular channels – Blood vessels through which cancer may spread.

white blood cells – Immune cells affected in leukaemia.

Comments