The Future of Rocketry: Beyond Chemical Propulsion

- Mr_Solid.Liquid.Gas

- Oct 29, 2025

- 3 min read

Chemical rockets opened space; they won’t take us comfortably across it.

To reach Mars faster, tour the outer planets efficiently, or even contemplate journeys to nearby stars, we need propulsion systems that trade brute chemical energy for sustained, high‑efficiency thrust.

From whisper‑quiet ion engines to photon‑pushed sails, from speculative fusion drives to the extreme promise and peril of antimatter, the next chapter of rocketry is about specific impulse, power density, and reliability over months and years—not minutes.

Electric Propulsion: Ion and Hall Thrusters

Electric propulsion converts electrical energy into kinetic energy of propellant.

Ion and Hall thrusters ionize a noble gas (often xenon) and accelerate it through electric or electromagnetic fields, producing a gentle but continuous push with extraordinarily high efficiency.

Their hallmark is high specific impulse—several times that of chemical engines—allowing spacecraft to achieve large velocity changes while carrying far less propellant.

The trade‑off is thrust.

Electric engines don’t deliver the explosive power needed for launch; they shine once in space, spiralling outward to new orbits and fine‑tuning trajectories.

With larger solar arrays or compact nuclear power sources, next‑gen electric propulsion can move heavier payloads, support rapid repositioning of satellites, and enable complex tours of multiple worlds on a single tank.

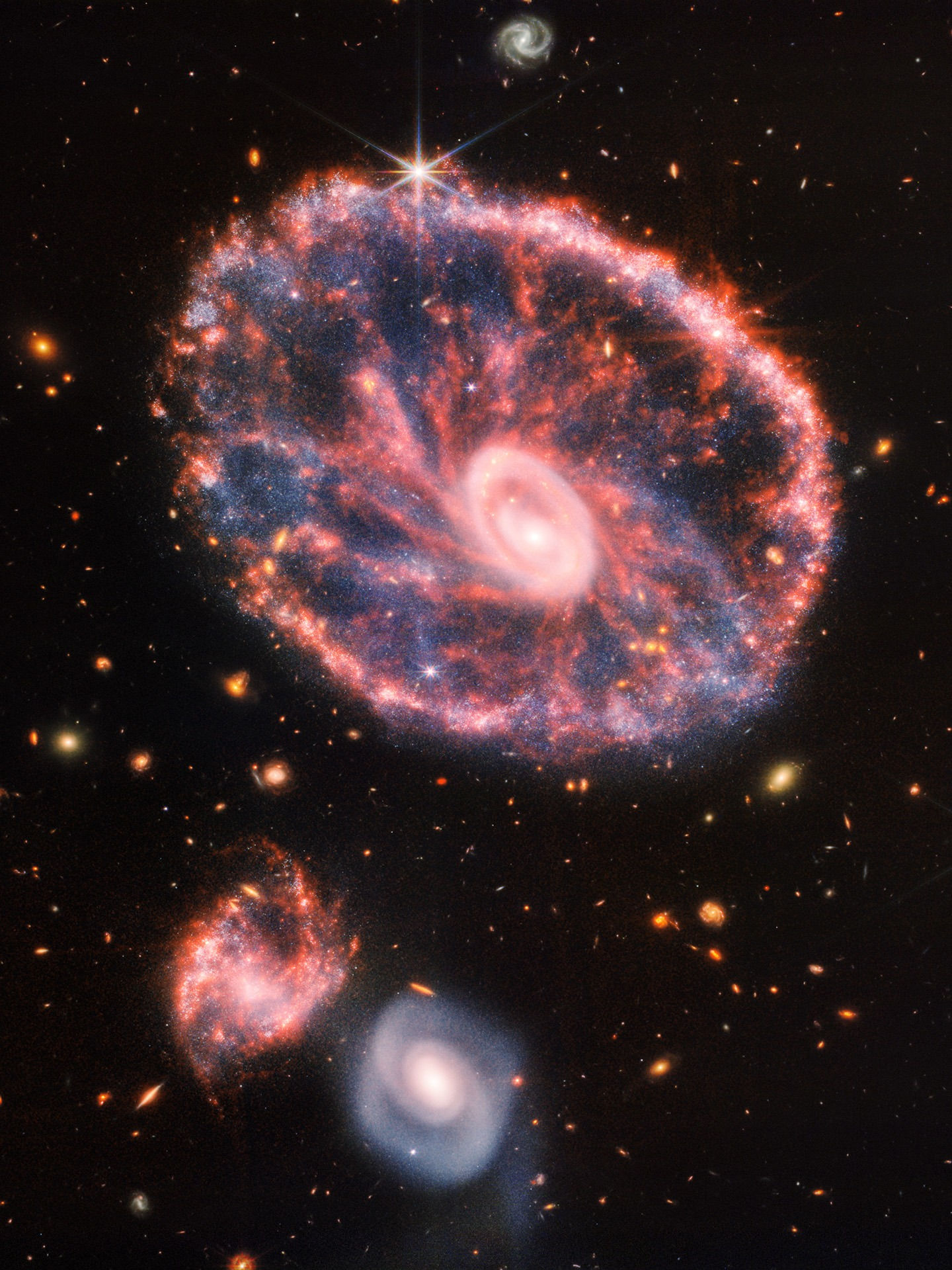

Fusion Drives: The Power of the Stars

Fusion propulsion aims to harness the same process that lights the Sun: fusing light nuclei to release vast energy.

Concepts range from pulsed fusion (micro‑explosions using lasers or magnetic compression) to steady‑state magnetically confined plasmas that direct exhaust through a magnetic nozzle.

If achieved, fusion drives could offer high thrust and extremely high specific impulse, shrinking interplanetary travel times dramatically.

Key challenges are ignition, stability, and power handling in a compact, space‑rated system.

Even partial progress—like fusion‑adjacent approaches that use aneutronic fuels or magnetized target fusion—could deliver step changes in performance.

A practical fusion stage would redraw mission design, turning month‑long burns into routine operations and opening fast logistics between planets.

Antimatter Engines and Limitations

Matter‑antimatter annihilation converts rest mass almost entirely into energy, making it the ultimate rocket fuel on paper.

Concepts include antimatter‑catalyzed fission/fusion—using tiny amounts of antimatter to trigger nuclear reactions—or direct annihilation engines that channel energetic particles into thrust.

The potential performance eclipses all chemical and most nuclear options.

Reality intervenes: producing and storing antimatter safely is extraordinarily difficult and energy‑intensive.

Magnetic or electrostatic traps can confine antiparticles, but scaling to mission‑useful quantities while preventing contact with normal matter remains a towering engineering challenge.

For the foreseeable future, antimatter is best viewed as a catalyst or research tool rather than a primary propellant.

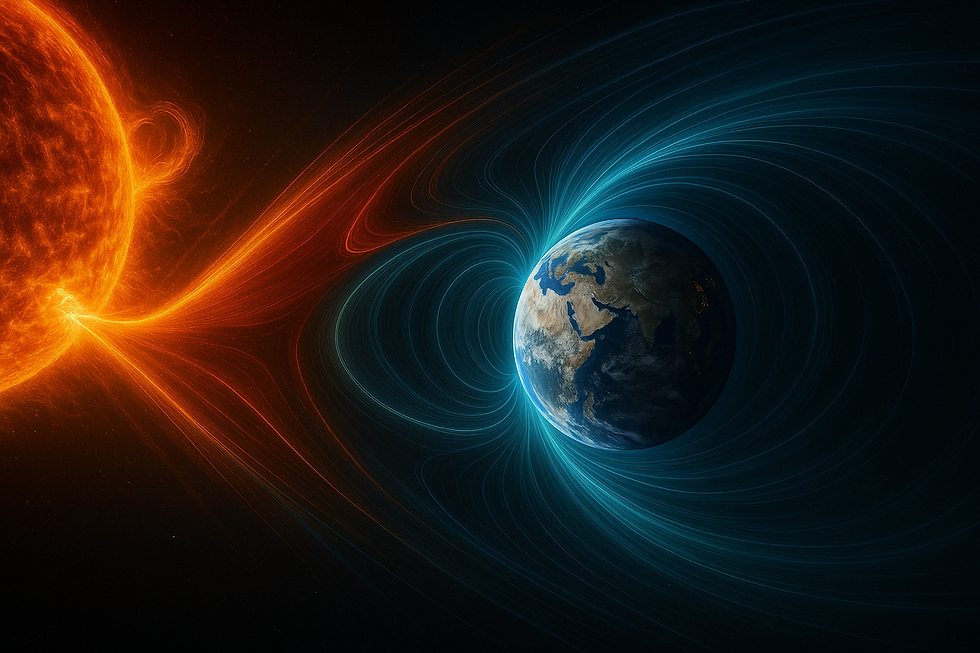

Solar Sails and Photon Propulsion

Photons carry momentum even though they have no mass.

Solar sails spread a large, ultra‑light reflective surface to catch sunlight, building speed without expending propellant.

Beamed‑energy sails replace sunlight with lasers or microwaves from Earth or orbital stations, enabling precise, high‑acceleration pushes for small probes.

Sailcraft demand exquisite materials—thin, durable films with controlled reflectivity—and high‑precision navigation to manage tacks and trim.

For interstellar precursors and rapid delivery of micro‑payloads, photon propulsion offers a uniquely scalable path: invest in infrastructure once, accelerate many missions.

Conclusion

The propulsion landscape ahead is plural.

Electric thrusters will be our workhorses, sails our sprinters for tiny payloads, and nuclear options—fission first, fusion if cracked—the backbone of fast, heavy transport.

Antimatter sits at the horizon as a lighthouse rather than a destination.

The common thread is efficiency: squeezing more delta‑v from every kilogram and every watt.

As power systems mature and in‑space manufacturing grows, the engines that carry us through the solar system will look less like fireworks—and more like precision tools tuned for the long haul.

Comments