The Fascinating Physics Behind Interstellar Travel

- Mr_Solid.Liquid.Gas

- Jul 4, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Jul 22, 2025

Science fiction has long served as a lens through which we explore the outer limits of possibility. From the warp drives of Star Trek to the psychic navigators of Dune, these imaginative concepts often stem from underlying scientific principles or hypotheses.

We’ll discuss why interstellar travel captivates humanity and how physics provides the framework to assess what's merely imaginative and what's technologically plausible.

Keywords: science fiction, physics inspiration, Star Trek, Dune, interstellar travel, technological plausibility

Understanding the Challenges of Interstellar Travel

Interstellar travel is not just about powerful engines; it's about contending with the fundamental laws of physics. One major challenge lies in Einstein's theory of special relativity, which addresses the limitations of traveling at light speed.

1. The Relativistic Roadblock: Gamma Factor & the Speed of Light

This section dives into the fundamentals of special relativity, focusing on the gamma factor (γ). This factor determines how time, mass, and energy change as velocity increases.

As an object approaches light speed, its mass effectively increases, demanding more energy for further acceleration. Furthermore, Newton's second law, when applied in relativistic contexts, culminates in the twins paradox. This scenario reveals time dilation, showcasing how aging is experienced differently when traveling at relativistic speeds.

Keywords: *gamma factor, special relativity, acceleration, mass increase, twins paradox, relativistic force*

The Significance of Gamma Factor

As an object approaches the speed of light, the gamma factor (γ) becomes significant. This factor, defined as γ = 1 / sqrt(1 - v²/c²), explains how time, length, and mass change for moving objects.

As the velocity (v) approaches the speed of light (c), gamma increases dramatically. This means time slows down for the traveler, while their mass effectively increases. Thus, further acceleration becomes increasingly difficult, requiring enormous amounts of energy to achieve.

Acceleration plays a central role here. Newton’s second law (F = ma) still holds, but with relativistic mass, we need to factor in changes in momentum. The force needed to maintain acceleration grows rapidly, making interstellar speeds impractical with current technology.

The 'Twins Paradox'

The famous twins paradox illustrates time dilation perfectly. If one twin travels near the speed of light and returns, they will have aged less than the twin who stayed on Earth.

This time dilation isn't just a theoretical idea; it's been confirmed with high-speed particles and atomic clocks aboard airplanes. Ultimately, the gamma factor sets a fundamental limit. It doesn't prohibit fast travel but demands we explore alternatives: warping space, wormholes, or becoming pure energy. Through understanding γ, we take the first step towards decoding our dream of the stars.

2. Folding Space and Breaking Boundaries

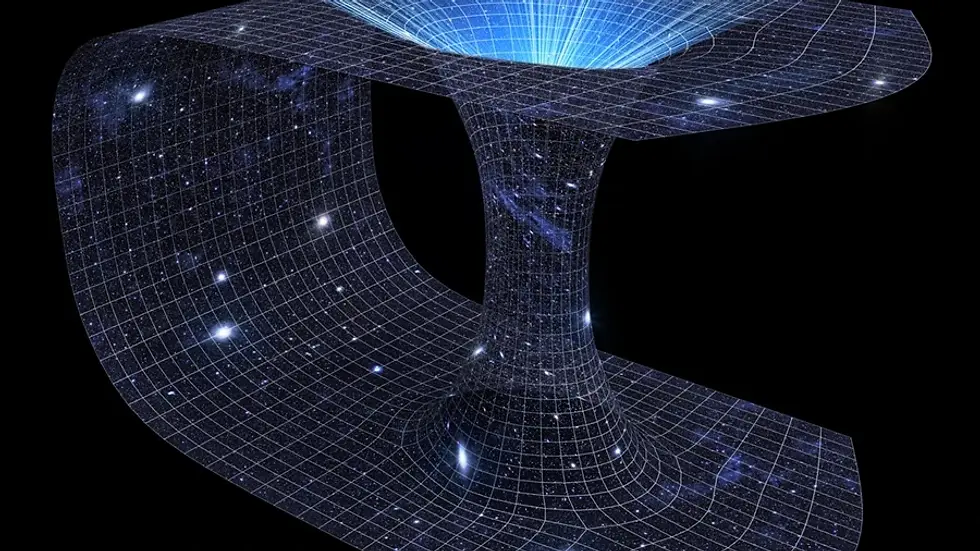

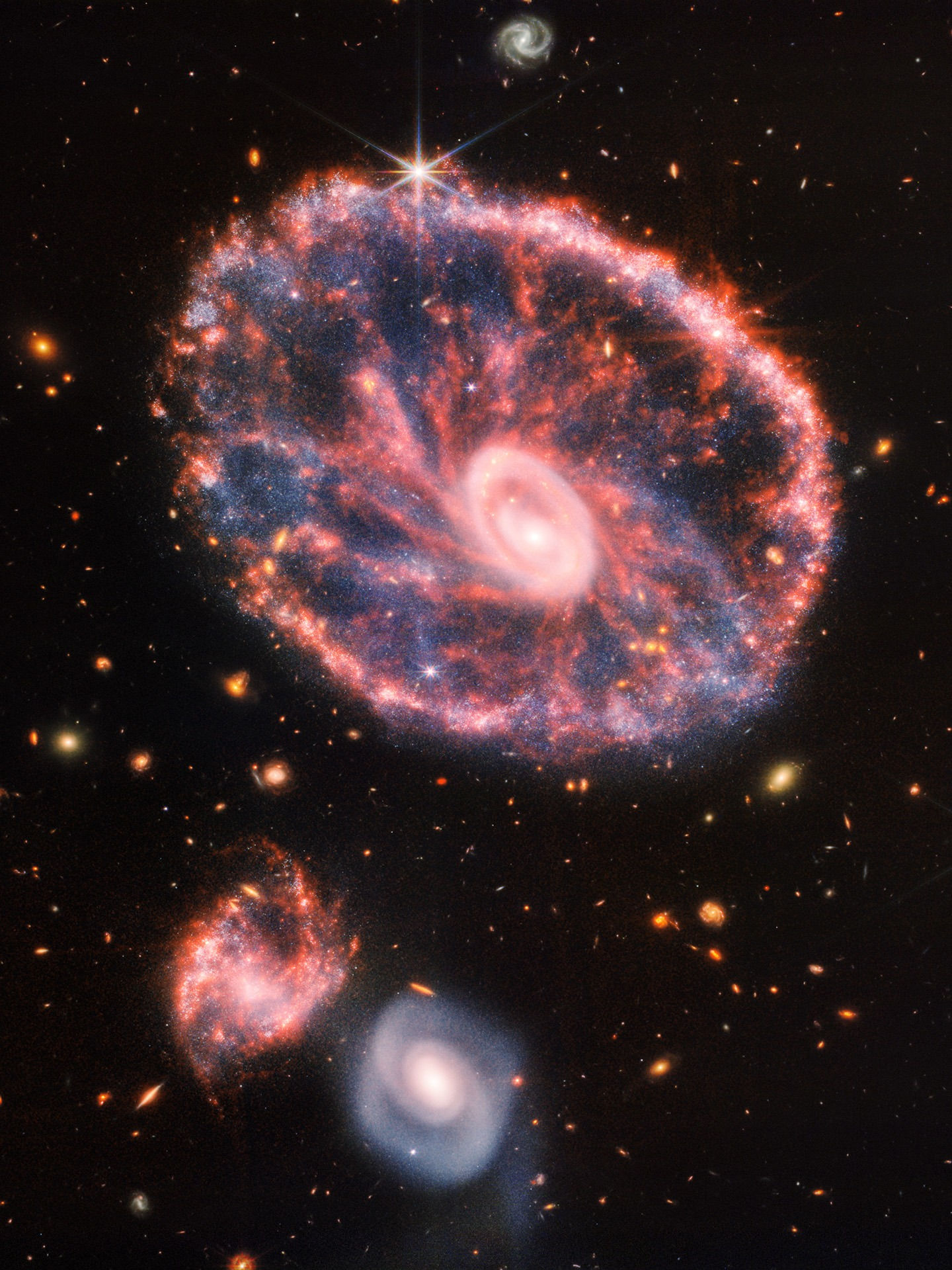

In this section, we explore concepts in general relativity and cosmology that create the theoretical possibility of folding space. This includes black holes, white holes, and wormholes.

We explain spacetime curvature and how extreme gravitational fields might connect distant points in the universe. Using visual analogies and current mathematical models, we evaluate whether traversable wormholes could be engineered.

Keywords: black holes, white holes, wormholes, spacetime curvature, general relativity, folding space

The Concept of Space Folding

To achieve interstellar distances quickly, some propose we fold space instead of traversing it. General relativity teaches us that massive objects cause spacetime to curve. This principle was confirmed when observing how light bends around stars.

Black Holes and Their Mysteries

Black holes are extreme examples of spacetime curvature, so dense that even light cannot escape.

Exploring the Theoretical: White Holes and Wormholes

White holes, the hypothetical opposites of black holes, would emit matter and energy.

A wormhole—a tunnel connecting two distant points in space—is an extrapolation of these concepts.

Traversable wormholes need negative energy or exotic matter—materials we have yet to find but aren't ruled out by theory.

Visualizing space as a two-dimensional sheet helps: a heavy mass causes a dip. By folding that sheet, you connect distant points—a shortcut through space. However, making that fold and keeping it stable presents a significant challenge.

Einstein-Rosen bridges and solutions from general relativity equations suggest these connections might exist. However, they may be too unstable, collapsing faster than anything could travel through them. Still, this exciting field of physics gives hope. If we can manipulate spacetime at the quantum level, we might create our tunnels—redefining travel.

3. Closer to Reality: What We Could Do Today

This section examines technologies that are the closest to reality today: nuclear propulsion and cryosleep.

Part A: Nuclear Propulsion

Nuclear propulsion is one of the most promising ideas for interstellar travel. Nuclear fission splits heavy atoms to release energy, while fusion combines light nuclei to achieve the same result—both yield tremendous energy.

Project Orion envisioned using nuclear bombs to propel a spacecraft by detonating them behind a pusher plate. Although politically and technically challenging, this idea remains one of the few options with enough power to leave our solar system.

Fusion, which fuels our Sun, could offer even more efficient propulsion. While experimental fusion reactors like ITER are showing progress, we are still years away from achieving the energy output required for spacecraft.

Part B: Cryosleep Technology

Complementing propulsion is the concept of cryosleep. Long journeys would necessitate humans surviving in a state of suspended animation. Hibernation patterns found in animals offer a model: some animals lower their body temperatures or enter torpor.

Scientists are studying how to induce similar states in humans. However, freezing cells poses significant problems.

Ice crystals can damage cell membranes, and enzymes may stop functioning properly at low temperatures. Prolonged freezing can lead to irreversible cell damage.

Cryoprotectants, such as glycerol, can help preserve cells, but they become toxic at high concentrations.

To make cryosleep viable, we must understand cellular repair and metabolic control to safely suspend enzymatic functions. If successful, this could allow multiple generations to travel asleep through space.

4. Peeking into the Future: Physics-Backed Possibilities

This section explores forward-looking ideas grounded in emerging science.

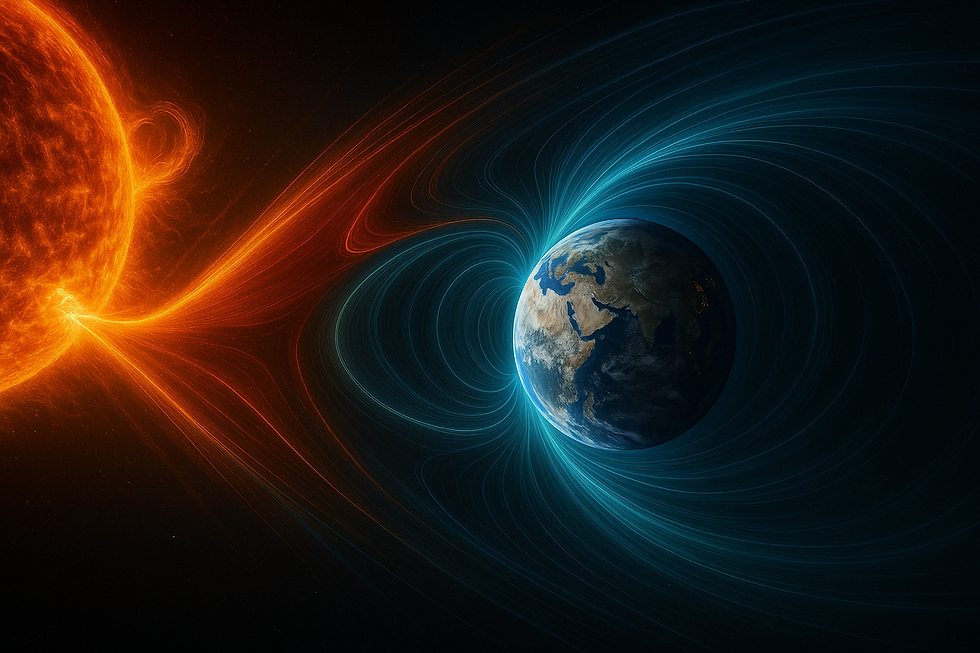

Part A: Solar Sails

Solar sails are among the simplest concepts: large, lightweight mirrors that catch photons from the Sun or lasers.

Despite having no mass, photons carry momentum. A giant sail could gradually accelerate a tiny spacecraft, as proposed by Breakthrough Starshot.

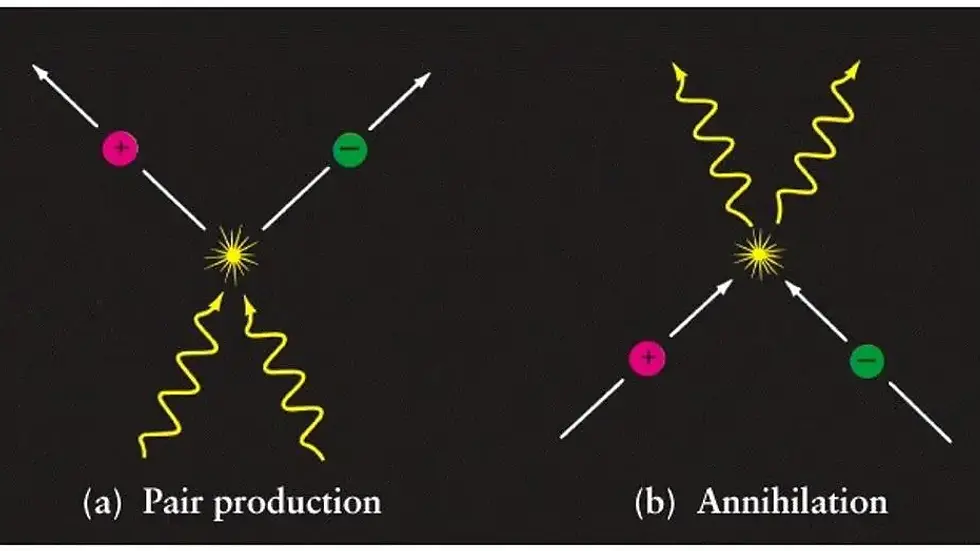

Part B: Antimatter Engines

Antimatter, when particles meet their antiparticles, annihilates into pure energy (E=mc²). CERN is studying antimatter, but producing and storing it is a significant challenge.

If mastered, antimatter could power engines thousands of times more efficiently than traditional chemical rockets.

Part C: Warp Bubble

Then there's the concept of the warp bubble, based on the Alcubierre drive. Rather than moving the ship itself, it contracts space ahead and expands it behind, allowing for distant travel without breaking the laws of relativity.

The challenge lies in the requirement for exotic matter and negative energy—neither of which is known to exist.

Part D: Matter-Energy Conversion

Lastly, could we convert matter into pure energy for transmission, echoing Sci-Fi concepts like teleportation in Star Trek?

While still speculative, it's grounded in quantum information theory, entanglement, and future ideas of matter-energy conversion. Physics may not allow us to break its rules, but it gives us tools to work around them, and those tools are still under development.

Conclusion: Physics as a Launchpad for Imagination

We reflect on how physics not only explains the universe but also fuels our imagination.

By studying the limits imposed by physical laws, we challenge ourselves to create new technologies. The relationship between theoretical exploration and creative speculation is symbiotic—imagination drives inquiry, and inquiry reshapes our imagination.

Whether interstellar travel comes in 100 or 1,000 years, our study of physics ensures that the conversation will never end.

Keywords: imagination, future technologies, creativity in science, physics and fiction, scientific curiosity

Glossary

Acceleration

The rate at which an object changes its velocity, often measured in meters per second squared (m/s²).

Alcubierre Drive

A speculative idea based on general relativity proposing a method of faster-than-light travel by contracting space in front of a ship and expanding it behind.

Antimatter

The mirror counterpart of normal matter. When matter and antimatter meet, they annihilate each other and release energy.

Atomic Clock

A highly precise clock that measures time based on the vibrations of atoms, often used to detect time dilation effects.

Black Hole

A region of spacetime with gravity so strong that nothing, not even light, can escape.

Breakthrough Starshot

A real-world initiative aiming to send microchip-sized probes to Alpha Centauri using solar sails pushed by high-powered lasers.

Cell Membrane

The protective outer layer of a cell controlling what enters and exits, sensitive to damage from freezing.

CERN

The European Organization for Nuclear Research, known for its experiments on antimatter and particle collisions.

Cryoprotectant

A chemical substance (e.g., glycerol) used to protect biological tissue from freezing damage.

Cryosleep

A theoretical state of suspended animation for humans, intended for long-duration space travel.

Enzyme

A protein acting as a catalyst in biological reactions, which can falter at extreme temperatures.

Exotic Matter

Hypothetical matter with unusual properties, such as negative mass or energy, required for stabilizing wormholes or warp drives.

Fission

A nuclear reaction where a heavy atomic nucleus splits into smaller parts, releasing significant energy.

Fusion

The process of combining light atomic nuclei (like hydrogen) into heavier ones (like helium) to release energy, powering stars.

Gamma Factor (γ)

A component of Einstein’s special relativity that describes changes in time, length, and mass as an object's speed approaches light speed.

General Relativity

Einstein’s theory describing gravity as the warping of spacetime by mass and energy.

Hibernation

A state of inactivity and metabolic depression in animals, used as a biological model for cryosleep.

Matter-Energy Conversion

The process of converting matter into pure energy, as expressed by Einstein’s equation E = mc².

Negative Energy

A hypothetical form of energy with properties opposite to normal energy, thought necessary for warp drives and wormholes.

Newton’s Second Law

A fundamental law of motion stating that force equals mass times acceleration (F = ma).

Photon

A particle of light with no mass but with energy and momentum, capable of exerting force on solar sails.

Project Orion

A conceptual spacecraft designed in the 20th century proposing the use of nuclear explosions for propulsion.

Relativistic Mass

The concept that an object’s mass increases as its speed approaches the speed of light, requiring more energy for further acceleration.

Solar Sail

A propulsion method involving large, reflective surfaces that capture momentum from light or lasers.

Special Relativity

Einstein’s theory describing the link between time and space for objects moving at constant speeds, especially those near light speed.

Spacetime

The four-dimensional continuum combining three dimensions of space with time, capable of being curved by mass and energy.

Time Dilation

A phenomenon predicted by relativity where time passes at different rates for moving and stationary observers.

Twins Paradox

A thought experiment in special relativity where a space-traveling twin ages more slowly than a sibling who remains on Earth due to time dilation.

Warp Bubble

A theoretical construct allowing a ship to move faster than light by distorting the surrounding spacetime.

White Hole

A hypothetical region of spacetime that expels matter and energy, considered the theoretical opposite of a black hole.

Wormhole

A speculative tunnel through spacetime connecting distant parts of the universe, theoretically allowing faster-than-light travel.

Comments